Chan first addressed the widespread misunderstanding of Tillich as a theologian who departed from Christian tradition. He noted that Tillich's interdisciplinary approach, which crosses boundaries between philosophy and theology, often creates confusion and leads to misinterpretation. Many label him as an existentialist or cultural theologian who allegedly abandoned Christian orthodoxy, but he argued this represents a fundamental misreading of Tillich's work.

Following this, Prof. Chan introduced his central thesis that Tillich's theology operates within a dynamic tension between "openness" and "commitment." Rather than abandoning tradition for contemporary relevance, Tillich demonstrates that genuine openness to modern culture requires a deep commitment to faith tradition, while authentic engagement with tradition demands openness to contemporary questions.

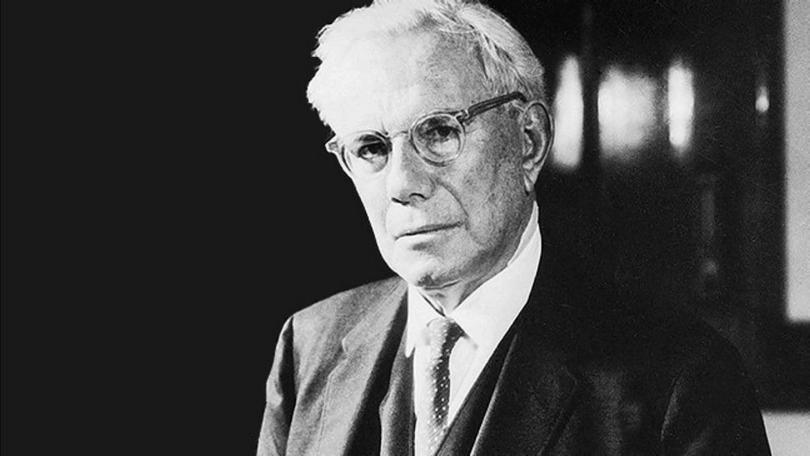

Subsequently, Prof. Chan provided biographical context essential for understanding Tillich's thought. Born in 1886 to a Lutheran pastor family in Germany, Tillich experienced two defining moments: 1914, when World War I transformed him from an academic theologian into an existentially-oriented thinker through his service as a military chaplain, and 1933, when Nazi persecution forced his emigration to the United States at the age of 47. Prof. Chan emphasized that Tillich's personal journey from Germany to the U.S. mirrors his theological movement from abstract speculation to existential engagement.

Prof. Chan then examined Tillich's self-description as living "on the boundary," clarifying that this does not mean "neither/nor" marginalization but rather "both/and" creative integration. Tillich positioned himself between theology and philosophy, church and society, conservative and radical perspectives, seeking to connect rather than separate these domains.

Moreover, Chan demonstrated how Tillich's major theological concepts are rooted in classical Christian traditions. First, he traced Tillich's "method of correlation" to the apologetic tradition of early Christian church fathers like Justin Martyr and Origen, who engaged Greek philosophy through the concept of "logos." Like these church fathers, Tillich sought common ground between faith and culture, arguing that theological answers must address real contemporary questions to remain meaningful.

Second, he connected Tillich's "Protestant principle" to the Reformation tradition of justification by faith. Tillich extended Luther's insight that finite beings cannot claim infinite status, applying this not only to ethical concerns but to all existence. His famous declaration that "not only he who is in sin, but also he who is in doubt is justified by faith" represents a radical extension of Reformation theology to address modern psychological struggles.

Third, the professor explored Tillich's concept of "theonomy" as reflecting appreciation for medieval Catholic synthesis. Tillich distinguished between heteronomy (external religious authority suppressing culture), autonomy (culture rejecting religious foundations), and theonomy (religious depth functioning as culture's inner essence). This shows his engagement with medieval traditions while addressing modern cultural challenges.

Finally, Prof. Chan addressed the most controversial aspect of Tillich's theology: his understanding of God. Many critics label Tillich as pantheistic for statements like "God is being-itself" and "God does not exist." However, Chan explained that Tillich operates within the "ontological type" of theological thinking, tracing from Plato through Augustine to medieval Franciscan tradition, which understands God not as "a being" among others but as the ground of all being.

Prof. Chan clarified that when Tillich says "God does not exist," he means God is not an object alongside other objects but rather the presupposition that makes all questioning possible. Using the metaphor of light, he explained that God enables us to see all things without being directly visible as an object of sight. This approach, far from being innovative, represents classical Christian mystical and philosophical traditions.

Furthermore, he emphasized that Tillich avoids simple pantheism by maintaining that discovering God as our deepest ground simultaneously reveals God's infinite transcendence. This unity of immanence and transcendence characterizes classical Christian theology rather than departing from it.

Finally, the speaker argued that Tillich's apparently radical theological innovations are deeply rooted in two millennia of Christian tradition. Rather than abandoning faith tradition, Tillich represents what Chan termed a "radical inheritor" who activates dormant potentials within classical Christianity. His theology demonstrates that genuine openness to contemporary culture requires the deepest possible commitment to faith tradition, while authentic tradition engagement demands courageous openness to modern questions and challenges.

Professor Chan concluded that understanding Tillich properly requires recognizing him not as a fashionable modern theologian who discarded tradition, but as a boundary-crossing thinker who found in classical Christian faith the resources necessary for engaging modernity. This challenges both conservative critics who dismiss Tillich as heterodox and liberal admirers who praise him for abandoning traditional Christianity.