The spread of a mysterious deadly disease emptied city streets and filled hospital beds.

Many risking their lives to help were people previously overlooked or even belittled.

Sound familiar?

The year was 1793, and yellow fever was ravaging Philadelphia — then the U.S. capital and the young nation’s largest city.

On a much smaller scale, the epidemic presented similar challenges to the COVID-19 pandemic. And just like now, church leaders found new ways to respond.

Two frontline heroes who stepped up to provide care were African American Methodist leaders — Richard Allen and Absalom Jones.

The two men wrote that “it was our duty to do all the good that we could to our suffering fellow mortals.”

They were acting “true to their Methodist convictions,” the historian Anna Louise Bates recounts in the April issue of Methodist History. Her essay, “Give Glory to God before He Cause Darkness,” details how Methodists including Allen and Jones responded to Philadelphia’s yellow fever outbreaks in the late 18th century.

Both men ultimately became pioneering leaders of new U.S. denominations. But in 1793, the two were licensed Methodist lay preachers, and their city was in trouble.

That August, the virus started sickening thousands in the bustling port city. Fear and financial hardship followed.

By the end of September, some 20,000 citizens had fled the city for safety. They included President George Washington, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and other U.S. government officials. The federal government basically ground to a halt.

However, most of Philadelphia’s residents remained, particularly those not affluent enough to move.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent Philadelphia physician and signer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, declared the city had an epidemic and turned to Allen and Jones for help.

The two men had won respect in the city. Born into slavery, both also had endured their share of hardship.

As a youngster, Allen saw his mother and two siblings sold away. He converted to Methodism at age 17 after hearing a white itinerant preacher denounce slavery. By doing extra work including support for the Revolutionary cause, Allen secured his freedom in 1783 and became an itinerant Methodist preacher.

He was one of two African Americans at the 1784 Christmas Conference that established the Methodist church in America. Jones bought his freedom that same year.

By the mid-1780s, both men were lay preachers whose evangelism was drawing black worshippers to what is now St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia. With that growth came tensions with the church’s white members. Matters came to head one Sunday when ushers tried to drag Jones and another black worshipper, as they knelt in prayer, to a segregated section. Allen recorded that the black congregants walked out en masse — many never to return.

In 1787, Jones and Allen helped form the Free African Society — a mutual aid society to assist free blacks and help slaves escape bondage. Jones made plans for African Americans to have their own church. About that time, they connected with Rush — the founding father — who had committed himself to the abolitionist cause.

When the epidemic took hold, Rush drew on their friendship to ask Allen and Jones to organize the African American community to care for the sick and dying.

No one knew at the time that mosquitoes spread the deadly fever that left victims with the telltale symptom of jaundice. And no one had a cure.

Rush wrongly thought black people were immune to the disease. He also suggested that by providing aid, the city’s black residents might win allies to their cause of freedom and equality.

The two men “agreed with Rush that this was maybe an opportunity to demonstrate black equality in a way that God made available,” historian Richard S. Newman told UM News. He is the author of the most recent biography of Richard Allen, “Freedom’s Prophet.”

Bates, a member of New Paltz United Methodist Church in New York, stressed the men’s religious motivation — particularly that of Allen. “Allen acted as a Methodist, first and foremost, and (with) a firm conviction that all souls were equal before God,” Bates wrote in her essay.

Invoking 1 John 4:20, Allen wrote: “I will relieve the necessities of my poor brethren, who are members of thy body; for he that loveth not his brother whom he has seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen?”

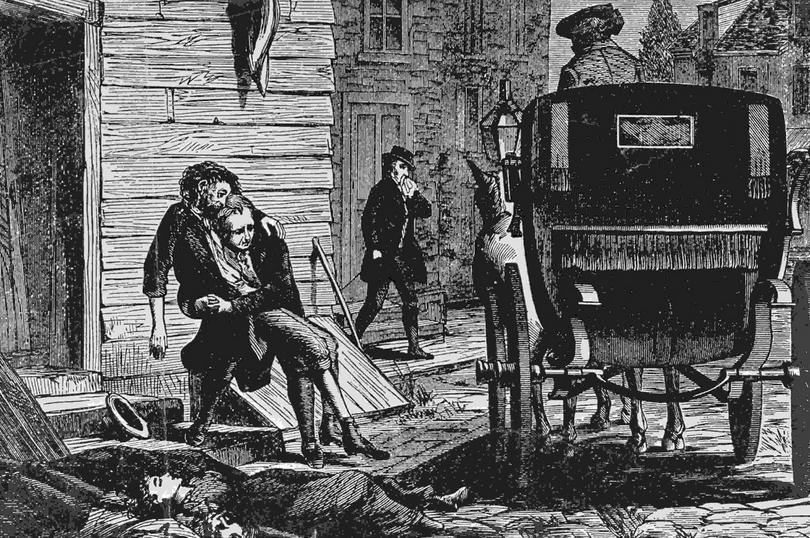

Under the leadership of Allen and Jones, members of the Free African Society and other black residents became first responders, nurses and gravediggers.

The work was groundbreaking in a city where slaves and slave owners were still a common sight, Newman said.

“They went into homes where whites were vulnerable and sick,” Newman said. Using Rush’s preferred treatment, they bled patients in an attempt to purge the pestilence. They also held patients’ hands and comforted them as they lay dying.

For their selflessness, these frontline heroes paid a price. Some 240 of the black workers got sick and died of the disease. Allen himself contracted the virus. While incapacitated, he still kept up with the efforts of African Americans to provide care and he ultimately pulled through.

Cooler weather killed the mosquitoes, and the disease subsided. By then, some 5,000 people, roughly a tenth of Philadelphia’s population, were dead.

Those who toiled so hard to save lives faced a backlash. African Americans were accused of causing needless death and even stealing from patients.

Allen and Jones jointly wrote a pamphlet defending the relief workers, which is how historians know so much of their thinking. The pamphlet also included a thorough accounting of payments and expenses.

The document bore the lengthy title, “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793 and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon them in some late Publications.” Newman said it left a legacy far longer than its name, becoming an inspiration for civil rights leaders as “a great moment in black protest.”

The Rev. Alfred T. Day, top executive of the United Methodist Commission on Archives and History, said the men offer an example for Christian discipleship that applies in confronting COVID-19.

“They had so experienced God’s love in their lives that they couldn’t sit by and watch people suffer,” said Day, who is a former pastor of St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia. “They also provided a powerful ministry of presence and compassion.”

Regardless of criticism, the U.S. National Library of Medicine sums up their action this way: “Philadelphia’s free African American residents kept the city from total collapse.”

Allen and Jones remained lifelong friends, but their response to the pervasive racism in the early U.S. took them in slightly different directions.

Jones would go on to become the first black ordained priest in the Episcopal Church and founding pastor of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Allen eventually would become the nation’s first black bishop as founder of a new Wesleyan denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The AME Church is now a full-communion partner of The United Methodist Church and a proposal is going forward for full communion with the Episcopal Church.

Today, the congregation Jones founded is providing food distribution for anyone in need because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The church is also a testing site for the coronavirus.

“The most important thing to learn from Jones and Allen is the importance of putting ministry into practice, i.e. ‘loving your neighbor,’” said the Very Rev. Martini Shaw, who leads the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. “Our neighbors include those infected and affected.”

Originally from: United Methodist News Service

CCD reprinted with permission.