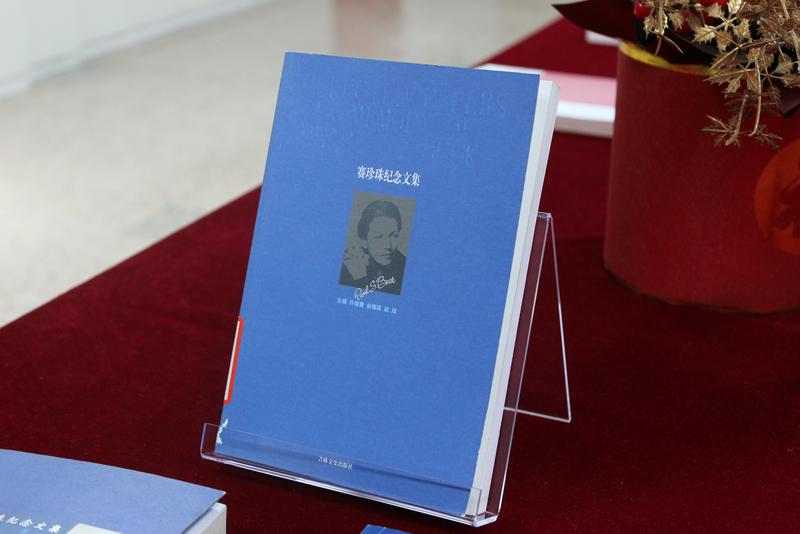

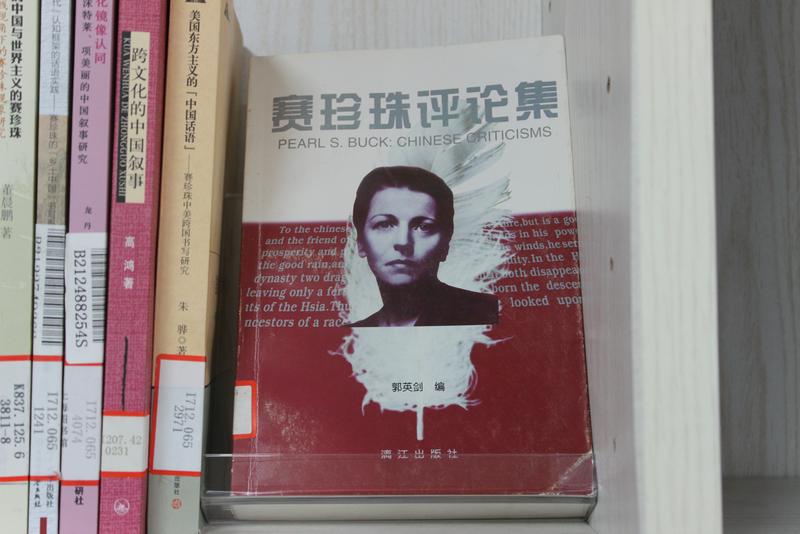

The Shanghai Library's current exhibition, "Pearls of the East, Harmony with the West," offers a concise yet detailed overview of Pearl S. Buck's life and legacy. Through a curated selection of her published works and scholarly studies, the exhibition presents a well-organized narrative of Buck's contributions to literature, translation, and intercultural dialogue.

Born in the United States but raised in China, Pearl S. Buck used literature as a bridge to span continents, connecting East and West. Her landmark novel The Good Earth earned her both the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize in Literature, making her the only American woman to receive both honors. Beyond these achievements, however, it was her sincere humanistic concern and deep cultural insight that opened a lasting window for the world to understand China.

Writing the Land: Literature Rooted in China's Soil

Pearl S. Buck's journey began in 1892, when she was brought to China as an infant by her missionary parents. By the age of two, she was already accompanying them on their travels through the country. This early immersion in both Chinese and English cultures fostered a deep attachment to the land and the people who labored on it. She learned about Chinese society and its rich traditions by living in rural villages and observing the lives of farmers. By 1900, Pearl was fluent in Chinese and fully integrated into the local environment.

Her formative years in China shaped her unique dual perspective, blending both Eastern and Western influences. Educated in both cultures, Pearl S. Buck was able to explain the complexities of Chinese life to a global audience. During her studies at Cornell University, her thesis on the Western influence on Chinese life won a prize, foreshadowing her future career as a cultural bridge. Upon returning to China, she continued her scholarly pursuits, studying Chinese literature under renowned scholars such as Long Moxiang, reading classical works like Water Margin and Dream of the Red Chamber, which deepened her understanding of the cultural nuances of Chinese society.

In 1917, after marrying agricultural expert John Lossing Buck, she lived alongside Chinese peasants in rural villages, gaining firsthand insight into their lives. This immersion provided her with the material that would later become the foundation of her literary masterpiece, The Good Earth. Through her deep empathy and dual cultural lens, she was able to capture the struggles of ordinary people, detailing their hardships, hopes, and resilience.

The Good Earth trilogy is a monumental work that not only describes the customs, family systems, and challenges of rural China, but also addresses issues such as marriage, women's rights, education, and the clash between Western and Chinese values. Her ability to balance both cultural perspectives allowed her to tell China's story with authenticity, while creating a profound connection between East and West.

Carrying China to the West: Work in Literary Translation

Among the most compelling parts of the exhibition was a tribute to Buck's work in literary translation, particularly her five-year effort to render Water Margin into English. Titled All Men Are Brothers, it was the first complete English version of this classical Chinese novel. Before publication, Buck traveled to Beijing, where she scoured old editions of the text and photographed hundreds of rare illustrations from ancient books, aiming to bring the translation closer to the original work. Her goal, as the exhibition explained, was not just to translate words but to faithfully transmit the spirit of a people and a tradition.

While the success of All Men Are Brothers marked a significant success in introducing Chinese literature to Western readers, Buck's translation ambitions did not stop there. One of her lifelong regrets was not being able to translate Dream of the Red Chamber. She later explained that the poetry in this novel, with its intricate rhyme and parallel structure, was impossible to translate faithfully, which led her to abandon the project.

Buck's approach to translation was deeply influenced by her cultural perspective. Her close connection to Chinese culture and her personal bonds with the Chinese people led her to show a sincere respect for the country's history and traditions. Thus, she chose the "foreignization" translation strategy, faithfully capturing the linguistic features of the original Chinese texts and presenting Chinese culture to Western culture in a manner that preserved its essence. Besides, stemming from her admiration and understanding of Chinese people and Chinese culture, her translations were not merely linguistic efforts but also a means of conveying China's social realities, offering a nuanced portrayal of Chinese life and values.

Promoting Cross-Cultural Understandings: Contributions as a Mediator

Born into a Western missionary family, raised in China, and later educated in both the United States and China, Buck found herself between two worlds. This dual cultural experience gave her a unique perspective, but also created an ongoing internal struggle to define and reconcile her cultural identity. As a cultural "marginal" figure, Buck's sense of displacement fueled her deep empathy and enabled her to become a genuine cultural mediator.

Buck's lifelong pursuit was the integration of Eastern and Western cultures. Her personal explorations led her to critically examine the values of both cultures. Her writings, speeches, and letters reflect her views on family, education, and gender, as well as her perspectives on the cultural exchange between China and the West. In particular, she believed that cultural exchange could only flourish if based on principles of equality, mutual benefit, and peace.

Buck's deep understanding of both Eastern and Western cultures shaped her contributions to literature and global communication. As a writer, she bridged civilizations, drawing on the strengths of both cultures to shape her work and worldview. In this sense, Pearl S. Buck's life and legacy stand as a powerful example of the potential for mutual understanding and collaboration across cultural divides.

As Zhou Enlai once said, "Pearl S. Buck was a renowned novelist and one of the Americans who understood China best. She held deep affection for the Chinese people... standing as a true friend of the Chinese people."