A century ago, the world still bore deep scars from the First World War. Communities lay in ruins, industrialization worsened inequality, and rapid modernization frayed social morals. Amid this turmoil, 670 church delegates—70 of them women—gathered in Stockholm in 1925 for the Life and Work Conference, seeking a collective social ethic to heal suffering and unite a divided humanity.

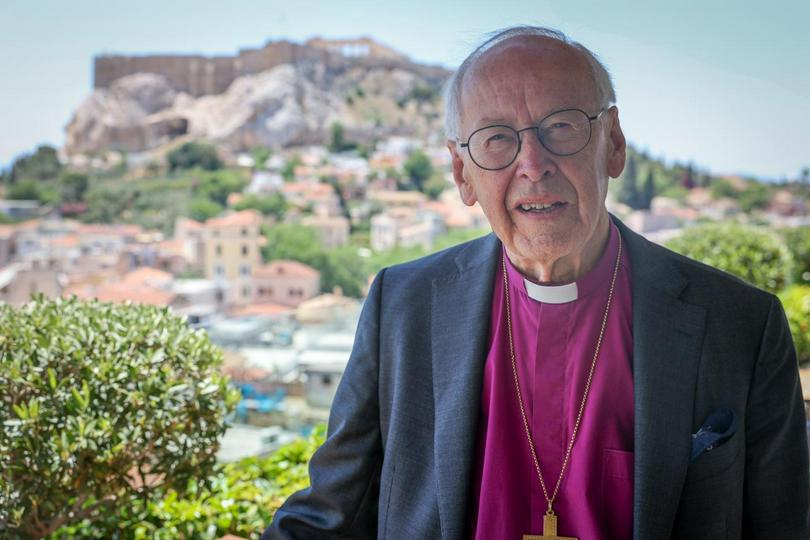

People were in a very good mood, but if you ask for the result of this meeting, you find next to nothing, said Jonas Jonson, bishop emeritus of the diocese of Strängnäs in the Church of Sweden.

After retiring, he spent years writing about the history of the ecumenical movement, including Ekumeniska pilgrimer (Ecumenical Pilgrims), which looks at why the 1925 conference mattered globally, and Nathan Söderblom: Called to Serve, a biography of the man who started the movement.

"For the time, the important thing in Stockholm 1925 was that the conference actually took place," he said.

The world was so fractured after World War I that even Christians found it impossible to see each other face-to-face. At that time, most European churches were national churches, intertwined with nationalist and wartime agendas.

"Germans and French, for instance, they really very distant from each other," Jonson explained. "It was almost miraculous that they got the whole conference together and met for more than a week."

Nathan Söderblom was the key person who made the miracle happen, the Archbishop of Uppsala in the Church of Sweden (appointed in 1914), and later a Nobel Peace Prize winner for organizing this conference.

At that time, Sweden's Lutheran church encompassed nearly the entire population. As Archbishop, Söderblom had ties across society. His push for unity began earlier with a small Christian group dedicated to bringing churches together and aiding those in need. In 1914, just as war broke out, 80 of them met in Constance, Germany, and formed a group called an alliance for promoting friendships among the people. The war halted gatherings, but members kept in touch by letter.

When they reconvened in the Netherlands in 1919, Söderblom shared his vision for an international church assembly—an ecumenical council speaking to the world. "It took him five years to plan this conference," Jonson said. "It was an incredible effort to do this, because most people were still so wounded by the war that they simply could not get together."

Jonson believes Söderblom succeeded because he was "the right man in the right place at the right time." Fluent in Swedish, French, German, and English, and able to read Latin and Greek, Söderblom was a professor of religious history, a musician, and a natural diplomat. His archives hold over 60,000 letters to contacts worldwide.

Sweden itself played a significant role as well. Having remained neutral during WWI, the country emerged unscathed and already modernized, with progressive reforms such as women's suffrage in place. "The whole nation of Sweden was really involved in this meeting," Jonson added. "Söderblom was able to knit all these things together. But I think he worked himself to death. He passed away only six years after the meeting in Stockholm."

The 1925 conference was a milestone for ecumenism in two key ways. First, it was the first global ecumenical gathering with elected delegates from churches—a break from earlier events like the 1910 Edinburgh Mission Conference or YMCA meetings, where delegates represented individuals or parachurch groups. "Since then, the ecumenical movement has primarily, in its institutional forms, been a church council," Jonson explained.

Second, it shifted the focus of Christian ethics. For decades, discussions had centered on individual morality; the Stockholm conference prioritized social ethics—addressing systemic issues like poverty, inequality, and war. "This stream of social ethical commitment since then often played a dominant role in the ecumenical discussions," Jonson said.

By 1948, Life and Work merged with Faith and Order (focused on doctrine and church structure) to form the World Council of Churches (WCC), which continues to advocate for peace and justice.

This year, the Church of Sweden marked the conference's centenary with an ecumenical week on August 18–25, themed "Time for God's peace"—a phrase as urgent now as in 1925.

A century ago, the idea of international justice and a rules-based world order was just starting. "When churches pushed for peace back then, they focused on building international institutions to uphold law and unite humanity," Jonson said. The conference argued for "compulsory arbitration"; nations facing conflict would resolve disputes peacefully before going to war. In the decades that followed, institutions like the United Nations and the WCC were built to realize that vision—with church support.

Today, that vision is under attack. "Multilateral institutions are being undermined by many nations; international law is ignored," Jonson said. "We have a new sort of ethnic nationalism that is creeping up again in Russia, the USA, and many other places. These days, it's hard to meet physically. So many countries do not let people in, and visas are denied, especially to young people."

"The most destructive thing you can think of in the world is when you get these nationalisms as an ideology and as a faith," Jonson said.

The dynamic of Christianity has also changed a lot. Since the 1960s, with the independence of African nations and so forth, African churches and others in the Global South have injected new energy and perspectives into ecumenism, helping to make oikumene—the whole inhabited world—a reality. Yet the resources of the ecumenical movement, including groups like the WCC, have dwindled.

China's story is a vivid thread in this 100-year narrative. Two Chinese delegates attended the 1925 conference. Mr. Gideon Cheng, better known as Cheng Jingyi, general secretary of the National Christian Council of China, and Miss Y. J. Fan, were listed in the official conference report.

"They really were noticed, because in 1925, they were so exotic," Jonson said. "Cheng was a very traveled man; he had been to many conferences around the world and played a good part in the Stockholm Conference." Young Chinese Christians, he added, were already making their voices heard in global groups like the World Student Christian Federation and the YMCA.

"The ecumenical movement has always been a movement of the young people," Jonson said. "One hundred years ago, the church in China was very much dominated by young people."

China's ecumenical journey continued; four Chinese churches were founding members of the WCC in 1948, though they withdrew during the Korean War. Membership was resumed in 1991 by the China Christian Council.

Jonson himself has long ties to China. In 1972, he defended his doctoral thesis on "Lutheran Missions in a Time of Revolution: The China Experience, 1944–1951." Later, at the Lutheran World Federation in Geneva, he worked on the encounter between Christianity and Marxism. Later in the 1970s, he was a recognized China expert in the Swedish church, authoring books on the country.

Troubled by the Church's conservatism and compromised mission practices, many young Swedish Christians in the late 1960s looked to the Third World for renewal. Alongside Latin American liberation theology, revolutionary China was viewed as a model of authentic egalitarianism.

Jonson shared this perspective. In 1972, he described China as "realizing programs the church had wished but failed to implement," with an ethic rivaling Christian morality. At the Louvain colloquium in 1974, he spoke of "the Chinese revolution as one stage in the fulfillment of God's salvific plan for the world," linking it to liberation theology. Later, in China: Church, Society, and Culture (1980), he argued that China had created living conditions more just than those in many Christian nations.

He witnessed the reopening of Shanghai's Mu'en (Moore Memorial) Church after the Cultural Revolution. "I saw thousands of people come to worship there after it had all been closed down during the Cultural Revolution," he said. " I have been in China mostly in those days of reconstruction, churches coming back on the public stage, being again part of the society, and being able to make their contribution to building the Chinese society. I think that whole process was so encouraging for the whole world."

He noted how quickly the church regained its footing: "It went very fast, suddenly, you had a leadership appearing that took the responsibility, held this whole thing together, and tried to form the church anew after all those years." During this time, Jonson developed a close personal friendship with Bishop K. H. Ting, one of the leading figures of China's Protestant church.

Jonson also recalled the Church of Sweden Mission's work in China. A small Swedish college was founded in Yi Yang, just north of Changsha. "The buildings are still there, preserved as a national heritage, built in Chinese style with all those symbols. I've visited a few times—it's one of those many memories of foreign missions in China."

He admitted that he is less familiar with the current state of the Chinese church. "There is much less published about China and the Chinese church in the West right now than there was 10 years ago, and I've been busy with other things." But he said, "The Chinese church, in total, is almost the largest individual church in the world. Also, it has a great heritage theologically, intellectually, and spiritually. I really prayed that the church of China will continue to be as strong, vital, faithful, and courageous, and once again, will play its full role in world Christianity."

As nationalism rises, Jonson looks back to Söderblom's teaching that the church has both a body and a soul—the body shaped by history and culture, the soul the common faith in Christ guided by the Holy Spirit.

"Diversity is fine, but division is evil," Jonson said."We must respect our differences while working together based on our common faith."

"The churches have to find ways, not only to survive, but to gain strength again, to contribute to multilateralism, which is multicultural, ecumenical, relational, and also in relation to nature, creation, and other religions," he said.

Reflecting on 100 years of ecumenism, Jonson calls the movement "a blessing, all the work of the Holy Spirit." The churches have changed incredibly. "When we met in Stockholm now, there is so much friendship, spontaneity. People meet as friends," he said, "In 1925, they were all suspicious of each other."

He recalled a beautiful moment during the ecumenical week: the Syrian Orthodox patriarch from Damascus sat on the ground, playing with children in a park in Stockholm.

For Jonson, the ecumenical movement is a movement of friendship. "Without personal relations, you get nowhere. If you turn this into a bureaucracy, it will die," he said. "I only hope that the borders will open again, and that people can travel freely and meet."