Robert and Linda Banks, an Australian couple, have spent the last 15 years researching the contributions of Australian women who lived and worked in China for nearly 50 years. They authored The Flower Mountain Quartet series, which includes four books on this topic.

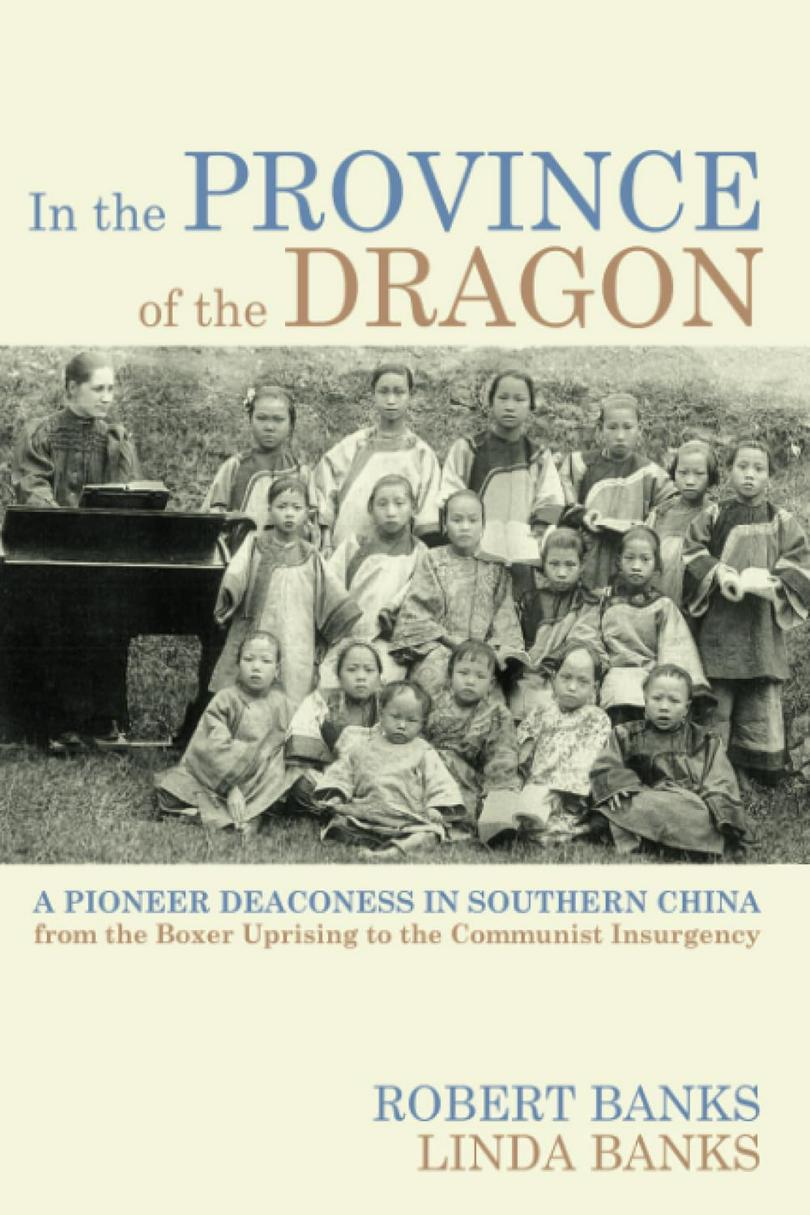

In an interview with China Christian Daily, they discussed their third book in the series, In the Province of the Dragon: A Pioneer Deaconess in Southern China from the Boxer Uprising to the Communist Insurgency, which tells the story of Robert's great aunt, Sophie Newton. Sophie arrived in China in 1897 and spent 35 years there. She returned to Australia in her mid-sixties due to health issues and passed away in 1958 at the age of 91.

Robert, a university and seminary teacher, focused on the role of God's people in the Bible, history, and the world. Linda, initially a school teacher, later became a pastor, working especially with international university students.

The idea for the book started when Robert was 15. He met Sophie not long before her passing, and she entrusted him with her journals, letters, photos, Bible, and devotional writings. Sophie encouraged Robert to tell her story, knowing his interest in history and faith. This moment later sparked their journey to write about her life.

In 2000, the archives of the Christian organization Sophie had worked with in China became available, coinciding with the digitization of local newspapers. They discovered about 150 articles on Sophie, including her lectures on China's people, culture, and society, which she had shared during her visits to Australia. The discovery led to their first trip to China, specifically to Fujian, where they found sites where Sophie had worked, some still standing despite their deterioration.

Before going to China, Sophie turned down a marriage proposal in Australia, feeling called to the mission field. She prepared by working in migrant churches with Chinese people and training at the Deaconess Institute in Sydney.

In Fuzhou, Sophie established schools for children, focusing on girls, whose education was limited at the time. She also set up women's training programs, helping them acquire skills to support their families. Sophie later founded a mission station in Fencheng, Fujian, which included a hospital, church, and guest quarters. She worked against social issues like infanticide, child marriage, foot binding, and opium addiction, and raised funds in Australia to support the education of orphaned girls in China.

Initially, female missionaries in Fuzhou worked under a male catechist and did not directly oversee the church. They supported the Chinese church structure by assisting the catechist and congregation in building and growing the church. Over time, as Sophie learned the language and culture, she became integrated into the wider church community, including churches in Fuzhou, not just the small village church.

Around 1917, a new progressive bishop from Ireland was appointed to Fuzhou. Sophie ensured that all meetings he had with local pastors were conducted in Chinese, not English, emphasizing that the church belonged to the Chinese people, not the West. In 1922, Sophie became the first Deaconess in the region. Her example inspired other women to pursue ministry, education, and healthcare roles, showing them they could serve God and make a contribution to society.

Robert noted two lessons from Sophie's ministry for today's cross-cultural workers. First, Sophie demonstrated a deep commitment to partnering with local believers, rather than seeking control. Second, Sophie's humility was key—she focused on meeting needs, not personal recognition, and often credited her success to God's work, not her own.

Sophie's time in China was marked by numerous challenges. The first was learning the local dialect, which was difficult even for native Chinese speakers. She passed her language exams but still needed the help of local people in the beginning.

Diseases like dysentery, typhoid, malaria, and cholera were prevalent. In addition to these environmental health risks, Sophie suffered from chronic migraines, which sometimes left her bedridden for days. She also had to deal with environmental dangers such as cyclones, epidemics, and the threat of bandits, though she remained mostly safe. Communication was another challenge, as letters from home took weeks to arrive. During this time, Sophie's mother's health declined, leaving Sophie feeling isolated.

Sophie served during a period of political unrest. In 1911, during the National Revolution, troops passed through her city and camped near the mission compound. Later, Sophie faced a direct threat from the son of a local warlord, but she handled the situation with grace, and it was resolved peacefully. During student protests in Fuzhou, Sophie and other missionaries had to evacuate temporarily, but they resumed their work once the situation calmed down.

Despite these challenges, Sophie relied on God's grace, which she documented in her journals. She had a strong support system, including Australian colleagues and local Chinese Christians, who treated each other like family. The local authorities were also helpful, offering protection and advice when needed.

Notably, Sophie's connection with the local people deepened over time. She helped train Bible women during a three-month residential Bible school, where she not only taught them, ate with them, but moved into their house where they were staying and lived with them. When Sophie visited villages, she often traveled with these Bible women, who helped teach her the language, introduce her to the culture, and make it acceptable for her visit to that village. Over time, she knew those people and the language.

Around ten years into her stay, Sophie met a woman who had been abandoned by her husband with two children and came to the mission station for help. Sophie, moved by compassion, adopted the two children and raised them as her own. The mother remained involved, but Sophie became an integral part of the family. A few years later, the children's mother unexpectedly passed away, leaving Sophie as their primary caregiver. This act of taking in a family and making them part of her own helped Sophie build deeper relationships with both the Chinese Christians at the mission station and the local community. "I think that was a very significant thing that took place in her life," Robert said.

Years later, during their time in Fuzhou, Robert and Linda met Mrs. Chen Maoring, one of the descendants of the two children Sophie had adopted. Mrs. Chen, who was 92 years old at the time, still referred to Sophie as "Grandma." Sophie had maintained a connection with her long after returning to Australia. Sophie had knitted jumpers for her, written letters, and prayed for her.

They also met other members of the extended family—around 30 to 40 people, from different age groups, gathered in a hotel lobby. The family shared an emotional moment. Mrs. Chen said that without Sophie adopting her father and aunt, none of these people would have even existed, let alone become Christians. Most of them are Christians today, and they live their lives in faith. Recalling the moment, Robert was moved, both laughing and crying.

Linda added that one of the most touching moments came from the 92-year-old woman, who shared that, even during the Cultural Revolution's toughest times, she had kept her faith alive in her heart. The lessons Sophie and the other missionaries had taught her as a child had stayed with her, sustaining her through life's most challenging moments.

Sophie's story was told in the third volume of The Flower Mountain Quartet. The first book, Children of the Massacre, recounts a 1895 uprising near Fuzhou, Fujian, where a local armed group sought independence during the Japanese invasion. The group attacked a mission base, killing nine missionaries and two children, including Robert Stewart. He and his wife, along with their two children, were killed. Over the next 30 years, six of the children from this missionary family felt called by God to return to China and serve as missionaries. This story inspired many Australian women, particularly Christians, to serve in China.

The second volume, They Shall See His Face, which has been translated into Chinese, tells the story of Amy Oxley Wilkinson. Amy established a renowned ministry for blind children in Fuzhou, earning a presidential award in China and recognition from the Queen of England. The Blind School she founded still exists today.

The fourth, Through the Valley of the Shadow, covers the experiences of eight Australian women who served in China during periods of conflict, including the Japanese invasion and the Chinese Civil War. They endured hardships such as being caught in crossfire, imprisoned, and physically deprived. These women worked in churches, hospitals, orphanages, schools, and relief centers, with some even being held for ransom by bandits for months before being rescued.

Robert hopes the remaining books in The Flower Mountain Quartet can be translated into Chinese. He believes this is important, as many Chinese and Australian Christians are unaware of this part of history. He wants to educate both the West and Chinese people, showing that while missionaries made mistakes and sometimes exhibited colonial attitudes, they genuinely loved the Chinese people and wanted to serve them.

Robert also shared a message for Chinese Christians: "Continue to serve not only by sharing the Christian message but also by addressing the practical needs of those who are poor, suffering from famine, floods, or other hardships across China. Just keep doing what you're doing—serving the Lord, serving the people, and serving the country."