Numerous Protestant and Catholic missionaries from the west came to preach the gospel in China, carrying with them different church traditions, social concepts, and personal views.

A short while ago, a believer shared some words that really generated my interest. In a WeChat group, the Christian posted, "Richard Wilhelm was a missionary, a pastor, and a bridge between eastern and western cultures. He came to China, but did not baptize anyone. I believe his calling in this life was to contribute to the cultural domain. He worked as a professor in Peking University and translated the 'I Ching'... thereby constructing a communication bridge between eastern and western cultures."

In contrast to famous missionaries such as Robert Morrison, Hudson Taylor, Richard Timothy, and John Leighton Stuart, Richard Wilhelm sounds very unfamiliar to many Chinese Christians. Wilhelm enjoys high reputation in the Chinese cultural and academic circles, acclaimed as " a great hero in the transmission of Chinese civilizations in the history of cultural exchanges between China and the West".

As a missionary

Born in Germany's Stuttgart on October 10, 1873, Richard Wilhelm was a missionary from the Weimar Mission. His father passed away when he was ten. To help him get rid of the family's difficult financial condition, his mother decided to let him become a Protestant pastor. He graduated from the seminary of the University of Tübingen in 1895 and twice held the post of interim pastor of the Tübingenin parish. In 1897, the Juye Incident broke out in Shandong and Germany's military wanted to use that opportunity to invade the Jiaozhou Bay in Qingdao. While German army occupied the bay, the Berlin Missionary Society and German Catholic Church sent missionaries to preach in Qingdao, including the General Evangelical Protestant Missionary Society that commissioned Richard Wilhelm to China.

During his 57-year life, Richard Wilhelm lived in China for more than 20 years. In 1899, he arrived in Qingdao; since then, he had an affinity with the new coastal city. His major focus was on education and medical areas, all while gradually showing interest in Chinese culture.

Influencing China by Running New Style Schools

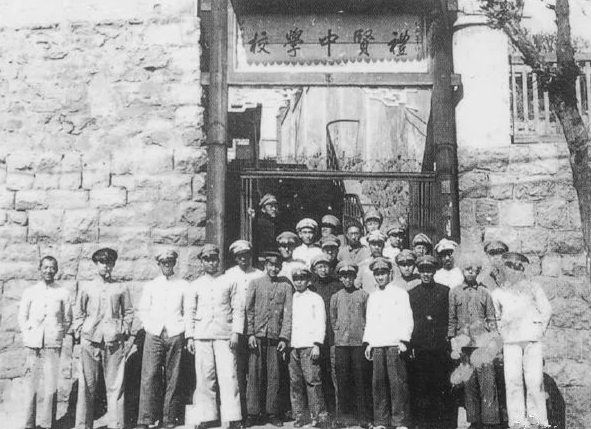

His greatest educational achievement in Qingdao was the founding of "Richard Wilhelm Schule". The school was opened on June 20, 1901 and had 70 students in five classes the next October. In the transitional period of the educational system, it became the model of new school education. Serving as its supervisor, Wilhelm also taught German, anatomy, and astronomy.

The school's fame soared as students came from the all 30 provinces of the country in 1906. Even dignitaries petitioned to allow their children to be enrolled. To commend him on his contributions, the Qing government awarded him an official position of the fourth rank.

He and his wife, Salome Blumhart, also built two girls' schools. In his eyes, it was crucial to make China "a gospel world" by providing equivalent wives for Chinese men who converted to Christianity.

Combining Chinese and Western teaching styles, the schools offered modern western courses and also Chinese cultural courses. The couple was attracted by the oriental world. Wilhelm changed to study Chinese culture and became famous for his German sinologist identity.

A Transmitter for Western and Eastern Cultural Exchanges

At that time, most western missionaries who had a biased sense of superiority of Western civilization more or less wanted to use Christian civilizations to transform the a so-called backward and uncultured faraway country in east Asia. However, Wilhelm could not speak any Chinese shortly after his arrival in Qingdao. He quickly realized that the missionaries would encounter the failure of the "ideal" evangelistic dream because there was no possibility to use Christianity in order to overcome Confucianism in such a wonderful eastern country. He knew he had just encountered a "respectable spiritual culture".

He was more interested in Chinese culture and thoughts than religion. To draw close to Chinese people, he claimed he was from Shandong and believed in Confucianism. He gave himself a Chinese name, "Wei Lixian". Later on, he translated several Chinese classics, including I Ching, Tao Te Ching, Zhuangzi and Liezi into German, and wrote many books about Chinese culture.

The most important one was his German translation of I Ching. In order to translate the classic, he grasped the cultural origins and historical backgrounds of the book, thereby becoming a "China hand". The German version is quite popular and has been reissued more than 20 times. Deemed as a recognized authorized version, Wilhelm's translation has been retranslated into many western languages and has gained tremendous influence in the western world.

Continuing Influence

Wilhelm was the most important Western sinologist in the early 20th century. He left a great heritage.

A book named Richard Wilhelm and Sinology, published in 2017, mentions that it collects reports about the sinologist by domestic and overseas scholars addressed in the First Chinese - German Forum in 2016 (Erstes Chinesisch - Deutsches Forum im Jahr 2016). They made a survey of Wilhelm's world of though through the perspectives of German literature, Chinese theology, intellectual history, and philosophy.

According to a report by Qingdao University, Wilhelm's granddaughter, Bettina Wilhelm, watched a documentary, "Wisdom of Changes - Richard Wilhelm and the I Ching", with professors and the university's lecturers and students on June 19, 2019. The documentary was about the life and work of this most distinguished translator and mediator in China, and how he translated several classical Chinese classic into German.

A famous scholar of new Confucianism mentions in one of his articles that Wilhelm became a disciple of Confucius when he left China, although he came to the country as a theologian and missionary. The scholar said his relief was that Wilhelm did not win any convert as a missionary.

Maybe there was a struggle in Wilhelm's heart. He confessed that he cared more about "forsaking his soul (conscience)". He studied Chinese culture with respect and appreciation, surpassing religious barriers, and this earned him more respect. I suppose that's the inspiration that this special missionary brings to us.

- Translated by Karen Luo