As China's close neighbor, Korea shares many cultural, social, and customary similarities with China. In the modern history of resisting colonial rule and striving for national independence, China and Korea were comrades-in-arms, sharing a common destiny. Looking back at this arduous history, Christianity played an irreplaceable role as the backbone of Korea's national independence movement.

March 1, 2024, marks the 105th anniversary of the 1919 Independence Movement of Korea. On the eve of this occasion, I had the opportunity to travel to Korea with a few friends for a historical pilgrimage. I visited the National Museum of Korea in central Seoul and the History Museum of Korean Christians at Soongsil University.

Reviewing the history of missionary work in Korea in the late 19th century, it becomes evident that Protestant Christianity entered the peninsula during a time of great upheaval when Korea was desperately seeking a new path forward. Western missionaries, adhering to the principles of "self-governance, self-support, and self-propagation," worked alongside local Korean evangelists. By using the Korean script (Hangul) to translate the Korean Bible, they launched a grassroots evangelization movement through education.

In this process, the gospel not only took root in ordinary households in a localized form but also subtly instilled the ideas of equality and freedom in many Koreans, laying the foundation for the later national independence movement.

However, Korea's geopolitical situation at the time was dire. Positioned at a strategic crossroads in Northeast Asia, the peninsula became a battleground for Russian and Japanese imperialist interests. Eventually, Korea slid into complete territorial occupation and loss of sovereignty.

At this moment of national crisis, many courageous individuals stepped forward to fight for independence and the restoration of their homeland. Among them, Christians formed a significant and indispensable force, acting as a catalyst for awakening national consciousness and spearheading the movement for national salvation.

The Awakening Voice—The Enlightenment Movement Led by The Independence newspaper

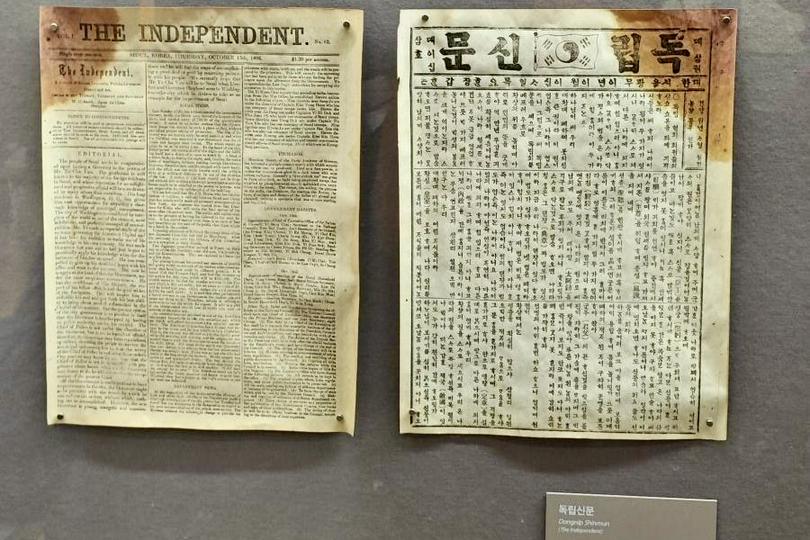

In the first exhibition hall of the National Museum of Korea, original Korean and English editions of Dongnipsinmun, or The Independence, Korea's first modern newspaper, are displayed. These old pages record the tireless effort and call of early patriotic Korean Christians to awaken their compatriots.

After China's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Joseon Dynasty lost faith in its longtime protector and turned its attention to the West, hoping to modernize by learning from Japan's Meiji Restoration. Despite Japan's manipulative interference in Korea's reform policies, this period was still a crucial step in Korea's modernization efforts.

During this time, Seo Jae-pil (Philip Jaisohn), a Korean Christian intellectual who had studied in the United States, sought to seize the opportunity for reform. He founded The Independence in 1896 as a public forum to raise awareness about national independence, equality, and freedom.

To reach the broader public, the newspaper was published entirely in Hangul, making it accessible even to those who had not received a classical Chinese education. Seo Jae-pil, as the chief editor, used Christian principles to introduce readers to Western political, economic, and cultural ideas. He also strongly condemned Russian colonial encroachments and criticized Korea's conservative royal factions. His work resonated deeply with the people.

According to Dr. Seo, whenever he spoke in public parks on Sundays, crowds would gather to support him, surprising not only the Korean emperor and conservative ministers but also foreign diplomats stationed in Korea.

Although The Independence was shut down after just two years due to opposition from conservative forces and foreign influences, it played a crucial role in uniting progressive Korean Christians and inspiring the public's desire for independence. This newspaper was the first clarion call for Korea's independence movement.

Christians Who Sacrificed Their Lives for Independence

In the early 20th century, under the weak rule of its last royal family and the administration of the notorious "traitorous" Prime Minister Lee Wan-yong, the Korean Empire successively signed the Eulsa Treaty or Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty in 1905 and the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty in 1910 with the ever-encroaching Japanese colonial invaders. These agreements gradually plunged Korea into a 35-year-long abyss of subjugation.

Following Korea's fall, the Japanese colonial government implemented a policy of cultural assimilation on the peninsula, aiming to eradicate Korean national identity by suppressing independent thought through cultural and ideological means. During this time, countless awakened independence fighters rose up, sacrificing their own lives to shoulder the responsibility of saving their nation from peril. They became the guiding force, leading the Korean people out of the suffering and oppression inflicted by Japanese colonial rule. They acted as the "Moses" of the common people.

Ahn Jung-geun: A Christian Patriot Who Gave His Life for Justice

Beneath the famous landmark Namsan Seoul Tower, a tall bronze statue stands in solemn silence. Dressed in a simple suit, his right arm raised, he gazes resolutely into the distance. He is none other than the anti-Japanese martyr forever remembered by the Chinese and Korean people, An Jung-geun.

Ahn Jung-geun was born in 1879 into a prestigious Korean family. His grandfather and father were both part of the yangban scholar-official class, which provided him with a strong foundation in Chinese classical studies and a broad worldview from an early age.

At the age of 15, An witnessed the Donghak Peasant Rebellion erupt in Korea. He and his father assisted the royal court in suppressing the uprising, and his bravery earned him recognition. However, his father was later falsely accused and persecuted by corrupt officials. To escape arrest, his father fled alone to the French Myeong-dong Cathedral, where he took refuge and converted to Christianity. After his father returned home safely, An was deeply influenced by him and also embraced Catholicism. In 1896, he was baptized, and from then on, his Christian faith became the spiritual pillar of his life, forming the foundation of his later theory of "Love of Heaven, the Nation, and the People" based on his idea of "On Peace in the East."

Following his conversion, the young Ahn Jung-geun was deeply pained by his nation's suffering at the hands of imperialist powers. He dedicated himself to establishing Western-style schools and promoting education as a means of awakening national consciousness. However, upon learning that Japan's then Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi had seized control of Korea through military force and brutally suppressed resistance movements, he made a life-changing decision: to abandon his educational efforts and take up arms against the colonial invaders. He actively participated in the righteous army movements launched by patriotic Koreans, leading his troops in fierce battles against the Japanese forces in pursuit of national independence.

Through prolonged struggles, Ahn Jung-geun came to a profound realization: the chaos in East Asia, Korea's subjugation, and the struggle for independence all stemmed from human arrogance, rivalry, and discord. He identified Itō Hirobumi as the chief culprit responsible for the region's turmoil. Without bringing him to justice, and without using this act to awaken the youth of East Asia, both Korea and the broader region would inevitably face destruction.

Thus, after months of careful preparation, on October 26, 1909, at Harbin Railway Station, Ahn Jung-geun assassinated Itō Hirobumi with a concealed pistol, firing the first shot in Korea's struggle against foreign invaders. This event triggered a wave of assassination attempts against puppet officials and high-ranking members of the Japanese colonial government in Korea. These actions not only weakened Japan's oppressive hold over Korea but also greatly inspired the Korean people, fueling their passion and confidence in the fight for independence.

Ahn Jung-geun was arrested but remained calm. In the days leading up to his execution, while imprisoned in Lvshun, he wrote several works advocating national independence and sovereignty restoration, including Autobiography of Ahn Eung-chil, A Treatise on Peace in the East, and "Thoughts of Ahn Eung-chil, the Korean." In "Thoughts of Ahn Eung-chil, the Korean", he invoked the idea of divine creation to emphasize that all people are born equal. He urged nations to uphold their innate virtues, respect morality, abandon conflicts, and peacefully enjoy their livelihoods on their own land. His writings reflect his vision of peace, deeply rooted in his Christian faith.

The March First Movement

Ahn Jung-geun's heroic act was like a spark that ignited the flames of anti-imperialist and patriotic movements among the peoples of China and Korea. It also illuminated the path forward for Korea's independence struggle. Following his sacrifice, Christianity, which had already taken root in Korea and accompanied its people through hardships, increasingly became a "national beacon" that awakened, united, protected, and guided the Korean people. This role became even more prominent during the March First Independence Movement of 1919, as Christianity shone across the entire Korean Peninsula, which had long been shrouded under Japanese oppression.

Even before the March First Movement, the Japanese colonial government had already intensified its brutal rule over Korea, implementing political, economic, and cultural exploitation on all fronts. From the moment Korea fell under Japanese control, the Church in Korea actively resisted by establishing nationalistic educational institutions, organizing mass gatherings, forming political groups, and even planning assassination attempts against colonial authorities. Within church communities, Korean Christians also found their own ways to resist the oppressors.

According to The History of the Korean Independence Movement, in the winter of 1905, the Korean Presbyterian Church organized a week-long national salvation prayer meeting, which was attended by thousands of people. In the following years, these prayer meetings expanded nationwide, evolving into a large-scale movement that united churches across the country. Meanwhile, despite Japan's oppressive policy which banned the Korean language, Korean Christians continued to hold secret worship services in their mother tongue, striving to preserve their linguistic and cultural heritage. Beyond religious gatherings, many churches also served as meeting places and shelters for independence activists and progressive youth by providing them with cover and protection.

This unwavering defiance of Japanese authority naturally provoked greater hostility from the colonial rulers, leading to intensified persecution of Christian churches. In 1915, the Japanese Governor-General of Korea enacted the "Missionary Regulations" and the "Revised Private School Act", imposing strict government control and surveillance over church activities and Christian schools. Japanese military police and law enforcement frequently raided and disrupted church gatherings. However, rather than dividing the Korean Christian community, these crackdowns instead became a catalyst for greater unity. In 1918, on the eve of the March First Movement, the Korean Presbyterian Church and the Methodist Church in Seoul formed a joint association, which later played a crucial leadership role in the independence movement.

On March 1, 1919, the state funeral of Korea's last emperor, Gojong (Yi Hee), served as the spark that ignited nationwide resistance. Sixteen Christian leaders joined forces with seventeen Buddhist and Cheondoist patriots to draft and sign the "Declaration of Independence." As thousands of mourners flooded into the capital for the funeral, the declaration spread rapidly, igniting an unprecedented surge of anti-Japanese nationalist sentiment across the entire Korean Peninsula. Within days, patriotic demonstrations known as the mansei protests erupted across the country, from Pyeongan Province in the north, near Changbai Mountain (borders with China), to Gyeonggi Province on the eastern seacoast.

Christians were not only initiators and leaders of the Movement but also some of its most active participants. During the two-month campaign, protests and gatherings occurred in 311 locations across Korea, with Christians directly leading or co-leading one-third of them. As a result, Korean Christianity bore an especially heavy burden of the blood cross. Churches and Christian schools were targeted and destroyed, and thousands of Christians were arrested, tortured, or even executed by the Japanese authorities. One of the most iconic figures of the movement, the young Christian student Yu Gwan-sun, known as the "Korean Joan of Arc," endured brutal torture in prison and sacrificed her life at just the age of 17.

Although the March First Movement was ultimately suppressed by Japanese military force within two months, it became a powerful source of inspiration for Korea's long struggle for independence. It also significantly strengthened Christianity's place within Korean society. No longer seen as a passive observer of national suffering, Christianity had become an active companion in Korea's fight for freedom. Through the sacrifices and devotion of both renowned and unsung Christian patriots across generations, Christianity became deeply embedded in the nation's identity, which ultimately shaped Korea's modern development and rise.

Walking with Christ Through Suffering

During my visit to the museums, the introduction given by a Korean Christian friend left a deep impression on me. He explained that Korea endured too much oppression, loss, and suffering throughout its history, shaping a national culture centered on a sense of "regret." This, in turn, has made the Korean people eager and earnest to seize every opportunity for salvation. It was precisely in the nation's most difficult and painful moments that the gospel of Christ reached this land, bringing comfort and hope for renewal to the Korean people.

At the same time, as they deeply understood 'regret' through their cultural experiences, Koreans could also profoundly empathize with the urgent love and sorrow of Jesus Christ on the cross. This enabled them to cherish the grace of salvation all the more and to respond with passionate devotion, dedicating themselves to the pursuit of national redemption, renewal, and revival.

As this brother rightly pointed out, when looking back at every stage of Korea's history, from its modern struggle for national independence to its transformation into a modern society, one can see a unique and powerful vitality that defines the Korean people—one that thrives in the midst of resistance and hardship. Behind this indomitable spirit lies the unwavering presence of faith, hope, love, and justice, the core Christian values that have walked hand in hand with Korean society throughout its journey.

- Translated by Charlie Li