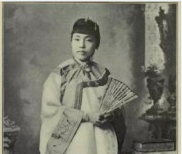

Hü King-eng (1865-1929), born in Fuzhou, was the first overseas student in Fujian Province. She was a Chinese female doctor in the first batch of overseas returnees and the first female representative of China to participate in international affairs.

Her life story began with her father, Hü Yangmei. Her father was a very devout Buddhist, while his brother first became a Christian. When he was trying to convert his Christian son, Hü Yangmei gradually came to know God and began to work hard for God. He later became a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church, where he remained until his death in 1893.

Hü King-eng’s mother grew up in a rich family in Fuzhou. After her father became a minister, they had to move frequently for the sake of evangelism. Her father had great regard for their place of birth and thought it a disaster for a man to move out of the birthplace. But as he was called by God, he accepted the arrangement without any scruple. Her mother was also willing to serve with her father.

When they left Fuzhou and visited the first people they came into contact with, her father saw piles of rubbish and dirty ditches in front of these people’s houses. In the houses, people, pigs, cattle, chickens and sheep lived in the same rooms. These people had no time to comb their hair, wash their faces and dress, and basically work in the fields for whole days.

Despite all the difficulties, their work paid off. Her mother was a warm-hearted sister who spread the gospel to those who had never heard it before. Neighborhood women began to come to her to hear the Gospel, and eventually, hundreds of people received it.

Hü King-eng was born in 1865, shortly after a period of severe persecution. It was customary for girls to bind their feet from an early age. But her father, a pastor, believed that this common and ancient custom was wrong. So he made a brave decision never seen before in the region: his daughter should have natural feet, and the bandage should be taken off. Later, she became an ardent advocate of natural foot and often recounted her experience as a pioneer of the natural foot movement in Fujian.

When she was old enough to go to school, Hü went to Uk Ing Girls' School, a boarding school run by the Methodist Episcopal Church. There was no music course at the school, but Hü was eager to learn how to play. Later, the wife of a missionary gave her lessons on her organ. After leaving the boarding school, she went to the Magaw Memorial Hospital, founded in 1877, which was the earliest and largest women’s and children’s hospital in China. Her adaptability to medical work and compassion for patients impressed Dr. Trask, then head of Magaw Memorial Hospital, who hoped she could get a more comprehensive education than she had received in Fuzhou. Therefore, she wrote a letter to the Executive Committee of the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society, praising Xü’s abilities and character and urging that arrangements be made for her to study in the United States. She could stay in the US for a decade if necessary, so that she could make a greater contribution when she returned.

Mrs. Keene, secretary of the Philadelphia chapter of the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society, was in charge of Xü’s travel arrangements. It was not easy for this young girl, who was only eighteen years old, to decide to leave her home and her country and go to study in a foreign country that was completely new to her. Her parents neither opposed her going nor encouraged her to go. Her parents told her at length about the loneliness she would experience in a foreign country, the perils of the long ocean voyage which she must undertake, and the situation she would face when she returned ten years later, at 28, well past her marriageable age.

But Xü, with strong faith and determination, said, “If God opens the door for me and calls me to go, I will go; otherwise, I’d rather work at home.” Her father said to her, “I can’t decide this for you. You must pray to God. If you decide to go, God will lead you.” She felt God say to her, “Don’t be afraid, for I will be with you no matter where you go.”

In the spring of 1884, Hü set foot on the journey to the United States. Upon arriving in New York, she immediately went to see Mrs. Keene in Philadelphia, where she met the Seitzes, who had come from Fuzhou, where she had known them since she was a child. She was in Philadelphia attending a meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and she spent the summer with them. Mr. and Mrs. Seitz helped Ms Hü learn English. When the fall semester began, Hü King-eng successfully entered Ohio Wesleyan University.

In April of Xü’s first year at Ohio Wesleyan, special meetings were held related to the university’s day of prayer, including one in the chapel where the university’s president and female faculty spoke. Minutes of the meeting show that Hü began to serve before returning to China. As soon as the female teacher, Miss Martin, finished speaking, Hü walked up to the podium, according to the transcript. Dressed in traditional Chinese dress, she stood elegantly in front of 600 young men and women to witness the wonderful work of Christ in her life. After hearing the testimony of Hü King-eng, the faith of many people was strengthened. One of her classmates gave an impressive statement: “Hü King-eng has a great influence on the girls and is usually more influential in leading people to Christ than any other girl in the school.”

One mother, visiting the school after her own daughter became a believer, said aloud, “When I gave money for our work in China, I didn’t expect that a Chinese girl would come to this country and bring my daughter to Christ.” Ms. Martin told the story of a student who for a long time refused all help but was willing to listen to Ms Xü. Eventually under Ms Xü’s guidance, she dedicated herself to the Lord, and later devoted her life to missionary work in Japan.

In four years, she completed classes at Ohio Wesleyan University, and in the fall of 1888, entered the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia, where she lived with her friend Mrs. Keene. Later, Hü became so ill that she decided to stop studying for a while and was going back to China, while her father was also sick in bed. Her lifelong friend, Sister Ruth Seitz, was also returning to Fuzhou.

Some wonder if living in the United States for so many years would have changed X, but she was not. No doubt in large part because of her calling at the time. A few years later, while saying goodbye to some girls who went to the United States for the first time, she said, “Some people don’t want girls to study in the United States because they think that when girls are educated, they will get proud. I don’t think we really have anything to be proud of. We Chinese girls have such a good chance to study abroad not because God loves us more than anyone else, but because God loves all of us Chinese. That is why He sent us first to learn about all the good things that we can do to help our people. The more we receive, the more we owe to the women and girls of China. So wherever we go, we have to think about how we can benefit our people and not become arrogant.”

In the fall of 1892, Hü re-entered the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia. She graduated on May 8, 1894. She spent the next year working in the hospital and was fortunate enough to be selected as a surgeon’s assistant at the Philadelphia General Clinic, which gave her the privilege of attending all the clinics and lectures.

In 1895, she returned to Fuzhou. She immediately began working at Magaw Hospital. Dr. Leon, who worked with her, reported at the end of the year, “She is not only our teacher but also a great inspiration to our students in living as a Christian.”

The next year, Dr. Leon took a leave to return to the United States, and let her take full responsibility for the hospital’s work. At the end of the year, her colleagues thought that sending Hü to the United States for medical education was one of the greatest blessings Fuzhou had ever received.

One missionary described her impression of Xü, “She was very busy at the hospital and at home, but she was always happy and helpful. Her love for Christians attracted the hearts of hundreds of suffering local women, who felt that every look and touch she made was a pity for them. Moreover, over the months, her humble manner and the gentle and quiet spirit with which she worked and prayed with us have greatly increased her popularity among her fellow missionaries here in Fuzhou.”

Around this time, Hü had the honor of being appointed by Li Hongzhang as one of two Chinese delegates to the World Congress on Women held in London in 1898.

She was not only a successful doctor but also a very good teacher in medical teaching and was well-liked by locals and foreigners alike. In 1899, Hü King-eng took over the Woolston Memorial Hospital.

The hospital is a women’s and children’s hospital, three miles from Fuzhou. During her first year at Woolston Memorial Hospital, two medical students were trained there, one of whom was her sister, Hü Shuhong. Hü once heard a patient said, “My own parents, brothers, and sisters would never be so patient and careful in taking care of me, especially when I’m sick. Your religion must be better than ours.” So despite the struggle, in the first year, Dr. Hü treated more than 2,600 patients.

Here, she had four main jobs: working at the pharmacy, working with hospital patients, visiting the homes of those too ill to come, and supervising the training of medical students. The hospital records tell many stories of what happened in the hospital.

There was once a man, belonging to a prominent family in the city, who brought an old man to be treated. Hospital rules were that only women and children could be hospitalized, so the doctor directed him to Dr. Kinnear’s hospital. But the old man looked very disappointed and pleaded pityingly: “I am a poor old man. My limbs are aching. Doctor, please help me. Don’t treat me like an adult. Treat me like a child.” Hü then made an exception to treat this old man. After he recovered, the old man regularly came to the hospital every day for morning prayers. After listening carefully for a few weeks, he said to the doctor, “Now I really know that this is a good religion and what I want, and I have decided to worship this God.”

A sick girl became happy and warm-hearted in hospital. When she came home from hospital, she said in the coming year, she hoped to return to the girls’ boarding school she was attending. At the same time, she was very eager to tell the people in her village the happy truths she had learned. “I will be the only Christian in the village, and I wish they could come and tell the people of our village about the Gospel.”

Work at the hospital had been progressing steadily since Hü took over. In 1904, she reported, “Our little medical school is doing very well. The success of the school is mainly attributed to our good teachers and the students themselves, who have a strong desire to learn. They took the written test this year, and the highest score was 98 while the lowest was 85.” The first student to receive a diploma from Woolston Memorial Hospital was Hü Shuhong, Hü King-eng’s younger sister, who graduated in April 1902.

The medical graduates were small in number, but they worked very hard and efficiently. Some of them stayed in the hospital as assistants or head nurses. In addition to her regular work as a doctor and teacher, Hü also paid great attention to evangelism. Every morning, there were morning prayers attended by hospital staff, hospital patients who were able to get out of bed, and sometimes a few visitors.

In addition to their morning meetings, the sisters who worked at the hospital often did evangelical work. They met in hospital wards, taught hospital patients to read the Bible, worked in hospital lines, and visited homes.

During the nine years she led Woolston Memorial Hospital, she worked almost nonstop and took few holidays. Like Lin Chao-chin, a female doctor in Fujian province known as the “mother of ten thousand babies”, Hü never married and devoted her whole life to the cause of medicine. In 1926, she left for Southeast Asia and died three years later in Singapore. She used to humbly say, “I just tell patients to ‘Please hold up your head and stretch out your hand’.”

Reference:

Margaret E. Burton《Notable Women of Modern China》(2005)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woolston_Memorial_Hospital

https://k.sina.cn/article_6750175107_192577f8300100drz9.html?from=history

https://www.dgkeheng.com/loupan/fxghlcp7mr

- Translated by Nicolas Cao