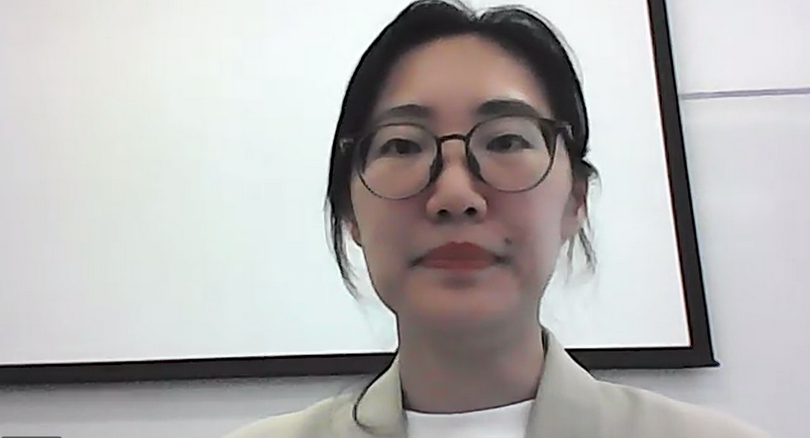

Dr. Wang Huiyu, associate professor in the Department of Philosophy at Sun Yat-sen University delivered a presentation titled "The Interpretation and Translation of Confucian Moral Concepts in the First Latin Translation of the Four Books," focusing on Michele Ruggieri's (1543-1607) pioneering Latin translation of the Confucian Four Books, specifically his handling of key ethical terms.

The presensation was part of a lecture titled "Catholicism in China: A Micro Perspective" as the inaugural event of the "Ecumenical Tradition Lecture Series" co-hosted by the Centre for Catholic Studies and the Centre for the Study of Religio us Ethics and Chinese Culture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong on March 1.

Dr. Wang began by outlining Ruggieri's life and missionary journey. Born in Italy in 1543, Ruggieri initially pursued legal studies and served in the court before joining the Society of Jesus. He arrived in Macau in 1579, where he dedicated himself to learning Chinese language and culture. This dedication eventually allowed him to enter China mainland. By 1583, he had established himself in Zhaoqing, marking the first Jesuit missionary base in China mainland. Dr. Wang emphasized Ruggieri's commitment to inculturation, highlighting his adoption of the Chinese name "Fuchu" (复初) and his wearing of a monk's robe when interacting with Chinese officials. This, however, was a strategic adaptation, not an attempt to syncretize Christianity with Buddhism.

The core of the presentation centered on Ruggieri's Latin translation of the Four Books—a groundbreaking achievement as the first complete translation of these foundational texts into a Western language. Dr. Wang noted that Ruggieri produced two versions: a Spanish translation presented to King Philip II of Spain, which included complete translations of the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, and selections from the Analects but omitted Mencius; and a more comprehensive Latin version containing all four books plus selections from the Mingxin Baojian. The Spanish translation was particularly significant given Ruggieri's connections to the Spanish court and the Spanish patronage of Jesuit missions. By presenting this work to Philip II, Ruggieri hoped to gain support for a more peaceful approach to China, countering voices in Europe advocating for military conquest as a means of evangelization. The Latin version, meanwhile, served as a more complete scholarly resource.

Dr. Wang meticulously analyzed Ruggieri's translation strategy. He used Zhu Xi's Sishu Zhangju Jizhu (or The Collected Commentaries on the Four Books) as his primary source. While striving for accuracy, Ruggieri also subtly incorporated elements of Catholic thought and biblical narrative style, aiming for a translation that was both faithful to the Confucian meaning and accessible to a Western audience.

To illustrate Ruggieri's approach, Dr. Wang examined his translation choices for key Confucian moral concepts:

Xing (性): Ruggieri translated xing as "natura." Dr. Wang presented the scholarly debate surrounding this choice, mentioning the arguments of scholars like Roger Ames, who suggests that "natura" carries unintended teleological connotations, and Liu Xiaogan, who defends the translation as capturing something stable yet dynamic in human nature. Ruggieri explained xing as both "the essence of life" and "the reason illuminated in human nature," incorporating Zhu Xi's commentary: "What people and things receive is the principle of life."

Xin (心): Ruggieri used both "animus" and "mens" to represent xin, reflecting its dual aspects of reason and emotion. This exemplifies his technique of using multiple Latin terms to convey the full meaning of a single Confucian concept.

Ren (仁): Ruggieri used "humanitas" and "pietas" to convey ren. The lecture pointed out that Ruggieri also incorporated the Christian concept of "loving one's neighbor" in his interpretation of ren.

Renzheng (仁政): For benevolent governance, Ruggieri used terms related to "pietas," such as "pius" or "piosissimus," highlighting the importance of benevolence in Confucian political thought.

Dr. Wang also discussed Ruggieri's characterization of Confucius and Mencius. He identified Mencius as a "philosophus" (philosopher) and "sapiens" (sage). For Confucius, Ruggieri used "philosophus" and, significantly, "sanctus" (saint) in the Latin Mengzi. This translation choice was particularly noteworthy given the complex religious implications of sainthood in Catholic tradition. Dr. Wang explained that in Chinese tradition, the concept of "shengren" (sage) evolved over centuries, gradually acquiring sacred dimensions, especially during the Song and Ming dynasties. While originally referring to someone with intellectual virtues and moral perfection, the veneration of Confucius increasingly took on religious characteristics, with similarities to Catholic saint veneration in terms of ritual ceremonies and canonical recognition. Ruggieri's use of "sanctus" for Confucius therefore created an intriguing ambiguity—it acknowledged Confucius's elevated status in Chinese tradition while potentially suggesting parallels with Christian sanctity. This translation choice reflected Ruggieri's balancing act between respecting Chinese philosophical traditions and making them comprehensible within a European religious framework, though it would later become a point of contention in Catholic circles regarding whether Confucius could truly be considered a "saint" without having received Christian grace.

The lecture also addressed the notable absence of the Mengzi in subsequent Jesuit translations for a considerable period. While Ruggieri's Latin version included the Mengzi, later Jesuit missionaries seemed less inclined to translate it. Dr. Wang explored potential reasons, including the inherent challenges of the Mengzi and the possible influence of "anti-Mencius" intellectual currents in late Ming and early Qing China. The suggestion was made that Matteo Ricci himself might have held reservations about Mencius, potentially influencing subsequent Jesuit translation efforts.

In conclusion, Dr. Wang emphasized the historical and scholarly significance of Ruggieri's Latin translation of the Four Books. She highlighted its role as a crucial milestone in Sino-Western cultural exchange and its enduring value as a resource for understanding both Confucian thought and the early interactions between China and the West. Despite the limitations of his time, Ruggieri demonstrated a deep respect for Chinese culture and a commitment to bridging the intellectual gap between East and West.