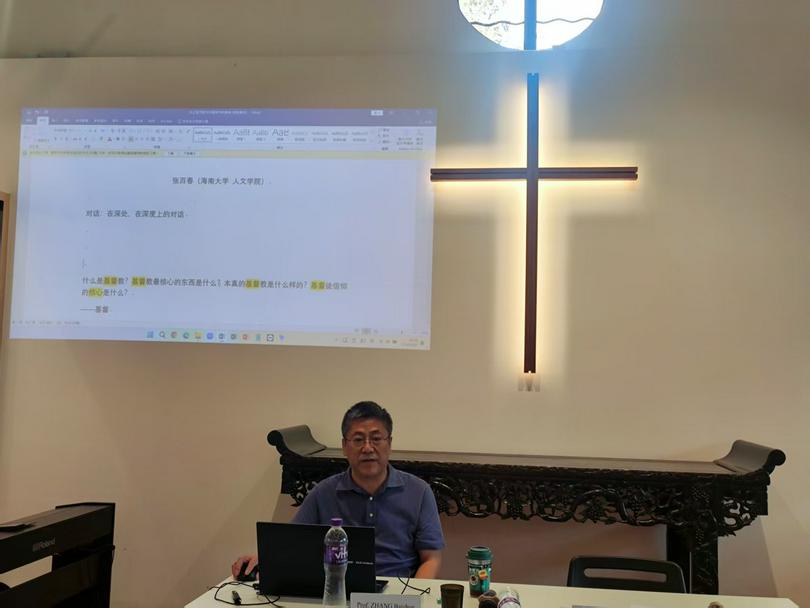

On April 17, during a study visit by faculty and students from the Divinity School of Chung Chi College, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Professor Zhang Baichun from Beijing Normal University delivered a lecture on the meaning and significance of Orthodox spirituality for Chinese academia at the Institute of Sino-Christian Studies (ISCS), Tao Fong Shan (TFS).

Professor Zhang opened by situating his perspective as a non-Christian scholar approaching Orthodox spirituality from an academic standpoint, while acknowledging his personal intellectual engagement with the subject. He emphasized that his exploration stemmed from scholarly curiosity and existential questioning rather than religious commitment. He framed his methodology as a "deep dialogue"—inspired by Russian thinker Mikhail Bakhtin and his mentor Sophrony the Athonite—where research emerges from an authentic connection to the subject while maintaining academic objectivity.

Applying this method to Christianity, Prof. Zhang identified this core unequivocally as Christ. However, he observed that in studying Christian doctrines (citing Summa Theologiae or Institutes of the Christian Religion as examples) or observing contemporary Christian life, the figure of Christ sometimes seemed obscured. To gain a clearer understanding, he turned to the New Testament, finding there a vivid depiction of Christ. He specifically referenced the story of Mary and Martha (Luke 10:38-42), interpreting Martha as representing engagement with many worldly tasks and concerns, while Mary, sitting at Jesus' feet, represents focus on the essential—"the one thing needful."

Prof. Zhang suggested this biblical narrative offers a framework for understanding different modes of spiritual engagement. He observed that most believers navigate between these two poles—the "Martha" mode of daily responsibilities and the "Mary" mode of spiritual focus, typically concentrated during specific religious observances. This led him to examine whether there exist individuals who maintain a more constant, focused spiritual orientation. His research identified Orthodox Christian monks as practitioners who dedicate themselves to sustained spiritual focus, though he was careful to note this observation came from his academic study, rather than personal religious experience.

The practice of these monks, Prof. Zhang explained, is Orthodox spirituality (often referred to as hesychasm). He defined it as a form of spiritual exercise or discipline aimed at gradual self-transformation, with the ultimate goal of achieving union with God through divine grace (theosis). He presented this union as the final objective of Christian faith, drawing a distinction between these monks and ordinary believers, characterizing the monks, through analogy, as "experts" or "100% Christians" in the sense that their entire lives are dedicated to this path, whereas others might live a "discounted" version due to worldly necessities. He emphasized this was an analogy about focus and specialization.

Prof. Zhang identified the core motivation behind this intense spiritual practice as the non-acceptance of death. Since death is a reality, the monks seek to overcome it by transforming themselves to unite with the resurrected Christ. He explained the logic: Christ, having ascended, is no longer physically present in the world in the same way. Therefore, for humans to connect with or unite with Christ, they must undergo a fundamental change. He used the Orthodox interpretation of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor as an illustration, where the emphasis is not solely on Christ changing, but on the disciples (Peter, James, John) gaining a new capacity or perception to see Christ's divine, uncreated light. This underscores the necessity of human transformation.

He outlined the traditional stages of this transformative path as understood in Orthodox spirituality: beginning with repentance, progressing through struggle against disordered attachments, and aiming toward purification. He presented these as the tradition's own developmental framework while maintaining his role as an academic observer rather than practitioner.

In conclusion, Prof. Zhang reflected on the personal significance of his research as a scholar outside the Christian tradition. The Orthodox monastic model, with its "vertical" orientation toward inner transformation, offered him a compelling alternative to the "horizontal" focus on material accumulation that dominates much of contemporary life. While not adopting the specific theological content, he found value in the structural example of dedicating one's life to pursuing what is most essential. He expressed appreciation for how his study of Orthodox spirituality had enriched his understanding of human possibilities while maintaining his intention to continue exploring these questions through dialogue with multiple philosophical and religious traditions.