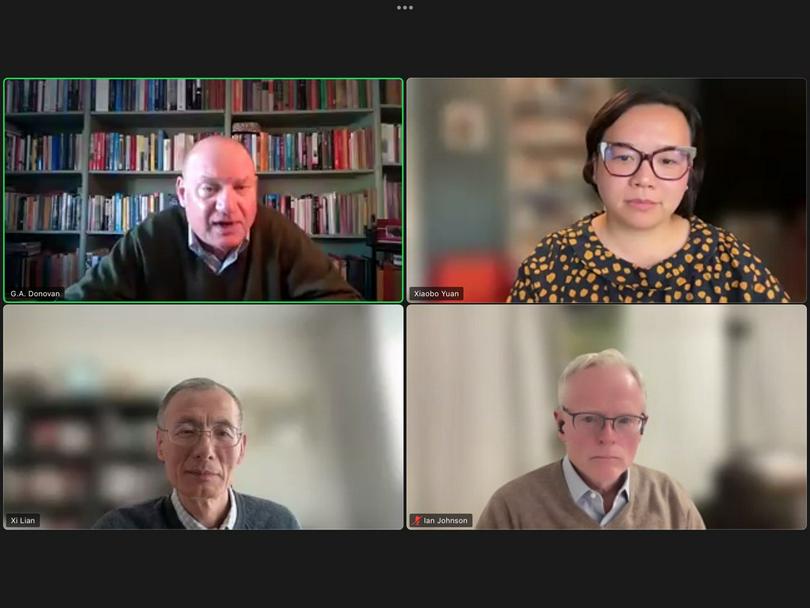

On November 19, the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis (CCA) hosted a virtual discussion on the evolving religious landscape in China, the reasons behind China’s spiritual revival, and the adaptations of faith communities regarding the increased government regulation.

The discussion “China’s Crisis of Faith and the Struggle Over Moral Authority” was moderated by CCA Fellow G.A. Donovan and featured Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ian Johnson, Duke Divinity School Professor Xi Lian, and Whitman College Assistant Professor Yuan Xiaobo.

Changes in China’s Religious Landscape

Ian Johnson, author of The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao, observed that the macro trends described in his 2017 book remain relevant today. Johnson noted that China has increasingly embraced traditional traits and values, supporting Buddhism, Taoism, and folk religions while showing some tolerance for Christianity and Islam. Over the past decade, this trend was in the context of a broader tightening of control over society, including restrictions on NGOs.

Yuan Xiaobo, assistant professor of anthropology and religion at Whitman College and a cultural anthropologist whose work explores the intersection of global Christianities, shared insights from her field research conducted in China before the COVID-19 pandemic. Her forthcoming book, Converting China: Urban Christianity and the Politics of Futurity, examines the future-making practices of state-sanctioned and underground Chinese Protestant churches.

Yuan’s research focused on urban house churches that aspired to transcend the traditional house church model. These churches formed larger networks with interconnected nodes in the city.

Even before COVID-19, churches operating outside official sanction had already developed creative strategies to navigate restrictions. For example, as new religious regulations introduced in 2018 tightened restrictions on renting venues to religious groups, many churches shifted their gatherings to smaller, private settings, such as individual homes, retreating from larger communal spaces.

Yuan noted that some churches viewed these adaptations as aligning with their theological conviction that churches weren't about physical spaces but the relationship to God. This conviction reinforced a sense of returning to the early church—a pure form of church, particularly in reformed or Calvinist-inflicted Christianity.

Xi Lian, David Steinmetz Distinguished professor of World Christianity at Duke Divinity School, pointed out the unique challenges faced by Christians, particularly since 2014 when China’s first national security blue book identified religious infiltration as a threat to socialism. In the same year, the sinicization of Christianity effort was officially launched, followed by the 2018 new religious affairs regulations.

He highlighted the resilience of Christianity despite escalating government crackdowns. He pointed to the example of a banned church that continues to hold weekly services, splitting into smaller cell groups and churches rather than meeting in a single location.

Reasons for Spiritual Revival in China

Yuan categorized three explanations for the rise of spirituality in China: a response to a crisis of belief, intersections between state projects and religion, and religion as a form of consumption.

The first explanation aligns with a common narrative about the surge in religious belief and practice following the transformative market reforms of the 1980s. Rapid social changes, coupled with intensifying alienation and competition, created a spiritual vacuum as shared communist ideology faded. Research among university students, entrepreneurs, and marginalized groups reveals that many turned to religion for consolation, stability, and solutions to economic and social precarity.

The second factor relates to the government’s use of religion as a tool for societal harmony. During Hu Jintao's administration, the goal of building a harmonious society leveraged religious infrastructures to restore social norms and order.

The third explanation frames religion as a form of identity expression akin to market consumption. Yuan noted examples like the urban trend of Western-style Christian weddings, which symbolize modernity and cosmopolitanism.

Yuan’s research focused on how religion helps people imagine and construct a desired future.

She further noted that the perceived religious revival in China depends on how religion is defined. Practices such as ancestor worship and tomb sweeping persisted even during the Mao era but may not have been categorized as "religion" at that time.

Johnson agreed, suggesting that the so-called "religious boom" may simply reflect a return to normal levels of practice after the suppression during the Mao era. He pointed out that religious engagement in contemporary China is more in line with secularized Western countries.

Johnson also noted the government’s use of intangible cultural heritage initiatives to reframe previously banned religious practices as cultural rather than religious, enabling limited government support while imposing conditions.

Adaptation to Increasing Regulation

Continuing his observations on Christianity in China, Lian discussed the various adaptations the Christian community has made in response to challenges.

Churches have divided into smaller groups, with much of their worship and Bible study activities shifting online. Additionally, Christian practices have extended beyond church walls into the public sphere, where theologians, human rights lawyers, citizen journalists, artists, and independent filmmakers bring Christian values into broader cultural discourse.

Lian highlighted the work of He Guanhu, a Christian theologian, philosopher, and cultural commentator who rose to prominence in the 1980s. In the internet age, He published books and collections of theological essays, introducing Christian perspectives and values into public discussions in ways that were previously unimaginable.

In his book Born in Sorrow, Grown in Grief: Selected Essays in Sino-Christian Theology (2021), He addressed pressing societal issues—such as the fragmentation of families, the erosion of community, and increasing individual isolation—from a Christian viewpoint.

Johnson noted that all religious groups in China, including those receiving some government favor, face greater difficulties today compared to 15 years ago. For instance, minors are entirely barred from participating in religious activities or entering places of worship. Johnson observed that many religious communities are adopting a "wait-and-see" approach, enduring the current environment while hoping for better conditions in the future.

Yuan added that while national-level policies regulate religion in China, their enforcement often depends on local contexts. Implementation is influenced by relationships between local officials and religious practitioners and can vary significantly across regions.