For observers of the church in China, the trajectory of international exchanges over the past three years has undergone a distinct transformation. What began as a rush of reconnection in 2023 evolved into a year of bold diplomatic breakthroughs in 2024 before settling into a new era of strategic prudence in 2025.

Data from public records and official statements between 2023 and 2025 show that the total volume of international exchanges in 2025 declined significantly. Rather than broad-spectrum engagement, the pattern moved toward more focused interaction, prioritizing specific multilateral platforms and regional partnerships.

2023: Restoring Traditional Channels

The year 2023 marked the resumption of in-person exchanges following three years of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. The data shows a clear priority: re-establish the baseline. The high volume of exchanges recorded that year was driven largely by a "return to the familiar."

One of the earliest areas of activity involved the return of functional partners closely tied to the church's daily ministry. In March, the United Bible Societies (UBS) was among the first international organizations to visit, focusing on issues related to scripture publication and supply chains. In May, the Foundation for Theological Education in Southeast Asia (FTESEA) visited Shanghai, signaling the restoration of academic and theological resource exchanges.

Traditional relationships with U.S. evangelical organizations were also actively re-engaged. The Luis Palau Association visited China in May, followed by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) in October, underscoring the continuity of these historically significant ties. China Partner likewise resumed its visits, meeting with the CCC&TSPM in Shanghai in September and visiting provincial Christian councils, such as Jiangxi, to consolidate longstanding relationships.

Regionally, exchanges in 2023 were particularly concentrated in the Greater Bay Area, with Hong Kong playing a prominent role. Delegations from the Hong Kong Chinese Christian Churches Union, the Baptist Convention of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Council of the Church of Christ in China, China Graduate School of Theology, and Christian Communications Ltd. made frequent visits to Guangdong and Shanghai.

At the same time, relationships with European partners began to thaw. The Friends of the Church in China from the UK visited Shanghai and Shaanxi in August and September. The Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) visited Shanghai in September, marking the return of major European denominational partners. While a member of the Russian Evangelical Alliance met with Rev. Wu Wei, president of the China Christian Council in November, a full delegation visit would not occur until the following year.

2024: A Global and Diverse Network

Entering 2024, the Chinese church moved beyond simple "recovery" to seek a substantive expansion of its diplomatic footprint. While the absolute number of visits did not see significant growth, the quality and level of engagement reached a new peak.

Two developments, in particular, defined the scope of church diplomacy in 2024. On July 24, the CCC&TSPM officially hosted a delegation from the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA). This visit marked a notable expansion of official dialogue beyond traditional ecumenical partners such as the World Council of Churches (WCC), extending engagement to the global evangelical community.

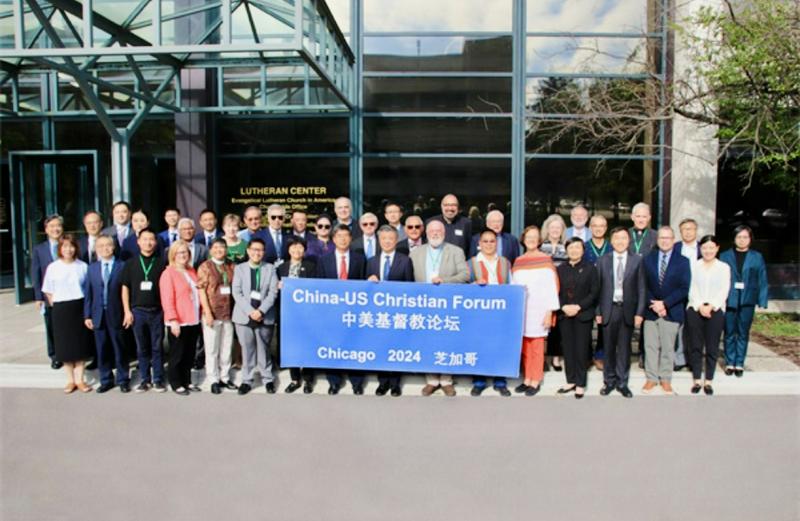

Later in the year, from August 26 to September 4, a Chinese church delegation traveled to the United States. CCC&TSPM co-hosted the "2024 China-US Christian Forum" with the North America Asia Pacific Forum (comprising Asia department heads from mainstream denominations in the US, Canada, and Australia). The delegation also visited seminaries, churches, and institutions in Chicago, Charlotte, and Atlanta.

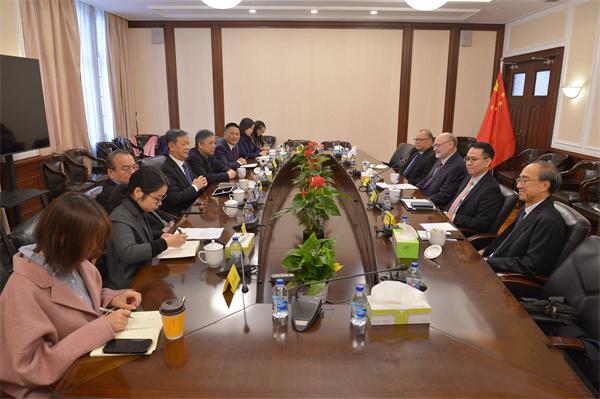

This reciprocal engagement continued in China on October 15-16, when the CCC&TSPM hosted a "China-US Christian Fellowship" at the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Shanghai.

Beyond the United States and the WEA, records from 2024 show a broad and diverse "circle of friends." From Europe, visitors included the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission, the Church of England, and continued delegations from German church partners. Exchanges with Russia also deepened, as a Chinese delegation met with Russian Protestant leaders in Shanghai in April, building on the individual contacts established the previous year.

Engagement across Asia remained robust. Delegations also arrived from the Korean Methodist Church and Trinity Theological College in Singapore. At the same time, Chinese delegations traveled abroad to participate in the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches in Egypt.

2025: Multilateralism and Asian Partnerships

Compared to the proactive stance of 2024, the data for 2025 shows a marked contraction, and a more prudent and precise "selection mode" emerged.

The most significant diplomatic event of the year occurred in November, when China hosted the World Council of Churches (WCC) Executive Committee meeting in Hangzhou. By concentrating resources on this major multilateral governance event, the Chinese church underscored its ongoing commitment to established global ecumenical mechanisms.

Another defining feature of 2025 was a noticeable pivot toward Southeast Asia. In April, the National Council of Churches of Singapore (NCCS) sent a delegation to China. From November 27 to 30, a delegation from a Chinese national theological seminary reciprocated with a visit to Trinity Theological College (TTC) in Singapore. In October, the Bible Society of Malaysia visited Shanghai and Nanjing.

At the provincial level, the Mission Covenant Church of Norway sustained its annual exchange with the Shaanxi CC&TSPM in late 2025. Such continuity indicates that historically rooted local partnerships can remain stable even as national-level engagement patterns fluctuate.

Rather than a simple expansion or contraction, the data points to a reconfiguration of priorities in how China's church engages internationally.

It is also important to note that changes in the pattern of international exchanges cannot be understood solely through the lens of church initiative. In the Chinese context, cross-border religious engagement operates within broader domestic and diplomatic frameworks, where regulatory priorities, geopolitical considerations, and institutional risk management play a significant role.